The Sufi Abu Madyan Shuaib Al-Tilimsani in the Literary and Folk Imagination

Issue 53

El Iwar Kamal, Algeria

Sufism passed through Algeria in five stages. The first was austerity, especially in the first two centuries after Hijrah, while the second stage followed the first. The third stage was about pure Sufism rather than asceticism and, in the fourth stage, Sufi orders emerged and their practices and rituals developed in the fifth century AH. This was followed by the final stage, which has lasted until the modern era, when Sufi rituals and practices became more prevalent and many Sufis started claiming that they could perform miracles. During this stage, Majzoubs appeared, as did the idea that the Divine can be found everywhere.

Sufism spread throughout Algeria, a crossroad and shrine inhabited by scholars, jurists and Sufis such as Abu Madyan Shuaib Al-Tilimsani, who settled in Bejaia. Ibn Arabi, who visited Algeria to meet with his Sheikh – Abu Madyan – influenced Algeria with his ‘Unity of Existence’ theory.

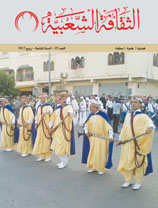

The spread of Sufism also explains the abundance of Sufi paths and Zawiyas. The most important orders include Rahmaniyyah, Qadiriyya, Shadhiliyya, Issawiyah, Daraqawiyyah, Senussiah, and Tijaniyyah.

The most important thing that the new Islam introduced to Northern Africa was a unity of language and belief that supported its ethnic, geographic and historical unity – a unity that both the Romans and the Christians of Rome and Byzantium failed to achieve.

Thanks to this unity of language and belief within the framework of Islam, the people of the region devoted themselves to building and cultural creativity in a time of political and economic freedom. The region established important cultural centres as prestigious as those in the Islamic East, including Kairouan, Fez, Tehrt, Al-Masila Asher, Qalat Beni Hammad, Bejaia, Marrakesh, Tlemcen, Constantine, and the important Islamic cities of Andalusia and Sicily.

In these cities, thought and trade flourished alongside agriculture, industry, the economy, urbanisation and social life. The populations grew, and there were innovations in all areas of civilisation.

Scientists, writers, poets, jurists, writers, intellectuals, philosophers and historians emerged in the region. These included Ibn Rashiq al-Masili, Sahnoun al-Qayrawani, Ibn Arafa al-Tunisi, Judge Ayyad al-Sabti, Sharif al-Sabti al-Idrisi, Ibn al Marzouq Al-Khatib, Al Hafid, Hafid al Hafid, Ibrahim Al-Abili, Ahmad Al-Maqri, Saeed Al-Aqbani, Ahmad Al-Ghubrini, Ahmad Bin Idris Al-Bajai, Abdul-Rahman Al-Waghlisi, Ibn Muata Al-Nahawi, Sheikh Ibn Marwan Al-Annabi, Abdul-Rahman Al-Thaalabi, Abdul-Rahman Ibn Khaldun and his brother Yahya, Abdul-Karim Al-Fakon, Yahya Al-Abdali, and Al-Hussain Al-Wartlani. These scholars helped to build and enrich the Arab-Islamic civilisation that led to Europe’s Renaissance.

Sufism went through two phases. During the sixth, seventh and eighth centuries, Sufism was taught at private schools and restricted to a specific class of educated people; it did not spread to the other classes settling in the major metropolitan areas of Tlemcen, Bejaia and Oran.This was followed by the period of folk mysticism, when Sufism shifted from the intellectuals to the common people and from theory to practice during the ninth century – this contributed to the emergence of Zawiyas and Ribats.

Sufism in Algeria (in the region previously known as the Middle Maghreb) began as a theory. In the 10th century AH, it became a practice, which was called the Sufism of the Sufi Zawiyas and Paths. One of the first Algerian Sufis was Sheikh Abu Madyan Shuaib bin Hassan al-Andalusi; both he and his teachings became widely known. His students Abd al-Salam ibn Mashish (who died in 655 AH) and Abu al-Hassan al-Shazly developed his teachings, establishing Shadhili, which became the point of origin for most Algerian orders.

In this article, we will focus on Sheikh Abu Madyan Al-Tilimsani’s influence on religious and scholarly circles, and the extent to which the folk imagination was inspired by his biography and influence. The paper also aims to explore the practice of seeking his blessings, which has sometimes resulted in miracles. He has been called ‘the Sheikh of all Sheikhs’, and his student Muhyiddin Ibn Arabi called him ‘the Teacher of Teachers’.